The True Cost Of Clothing The World

Last week marked the fifth year since the Rana Plaza tragedy in Dhaka which killed more than 1,000 garment workers and injured thousands more when a five-storey building collapsed on them.

The groundswell of protests that followed prodded the world to sit up and take notice of the workings of the fast fashion industry and the social and environmental costs of dressing the world. Most significantly, it led to the launch of Fashion Revolution, a movement to reform the way our clothes are sourced, produced and consumed, so that they are made in ways that are cleaner, fairer and safer for people and the planet. Under the scrutiny of the movement was exposed an industry plagued by an overworked, underpaid workforce, exploitative practices, overuse of fossil fuels, chemical pollution of water bodies, an ever-increasing burden of waste from discarded garments, and the snuffing out of local economies in developing countries by an influx of secondhand clothing.

The Revolution was a clarion call for a reshaping of the global fashion value chain; it demanded fairer prices for the farmer and urged consumers to get their favourite brands to clean up their act.

Organic cotton farmers are a crucial part of Fairtrade supply chains

With the arrival of GM seeds, chemical inputs, mono-cropping and climate change, farmers’ cost structures have changed. On the one hand, they are forced to take expensive loans to buy seeds and chemical inputs sold by multinational corporations. On the other, market forces keep product prices low by squeezing those at the bottom of the supply chain with low revenues.

This gives rise to India’s cotton paradox: it is the world’s largest producer and second largest exporter of cotton, yet the cotton growing belt has the highest number of farm suicides - the largest sustained wave of such deaths recorded in history. In many countries, cotton is also the biggest user of agricultural chemicals. In India, farmers untrained in scientific pest management regularly die of exposure to toxic chemicals (often those banned in other countries), which ultimately make their way into our clothes, into the food chain through cotton seed oil, and into the soil and water.

Our choices as consumers could change the way fashion is produced

Since it was launched in India in 2013, Fairtrade has been working towards building a domestic market for products made sustainably in India following better, more equitable labour and environmental standards.

In India, it works with farmer producer organisations or collectives who upon undergoing an audit and paying for certification, are assured a minimum purchase price – that never falls below market level - together with training to revive traditional farming practices, access to organic inputs, and non-GM seeds. Collectives that get their produce Fairtrade certified commit to uphold Fairtrade Standards which guarantee them improved bargaining power through better terms of trade and an added premium, negotiated with brands before cultivation begins. Farmers can invest the premium in community development or environmental projects such as building roads and wells or buying educational equipment.

“As consumers, we don’t know the impact of our purchase decisions, so we're unknowingly or unwillingly supporting practices like child labour and pollution that keep prices low."

To increase domestic supply of clean fashion, Fairtrade also partners with clothing companies that uphold local sustainability, support primary producers by buying their cotton at remunerative prices and build ethical supply chains that provide a living wage and good working conditions. Among other things, Fairtrade principles outlaw the use of GMOs and chemicals included in the Fairtrade Prohibited Materials List, and require brands to pledge to minimise the use of pesticides. Says Abhishek Jani, CEO - Fairtrade India, “A strong overlap with organic agriculture promises better benefits at the farm level.” Up the value chain, zero liquid discharge norms prohibit garment factories from releasing chemicals that threaten to pollute soil, surface and groundwater, he adds.

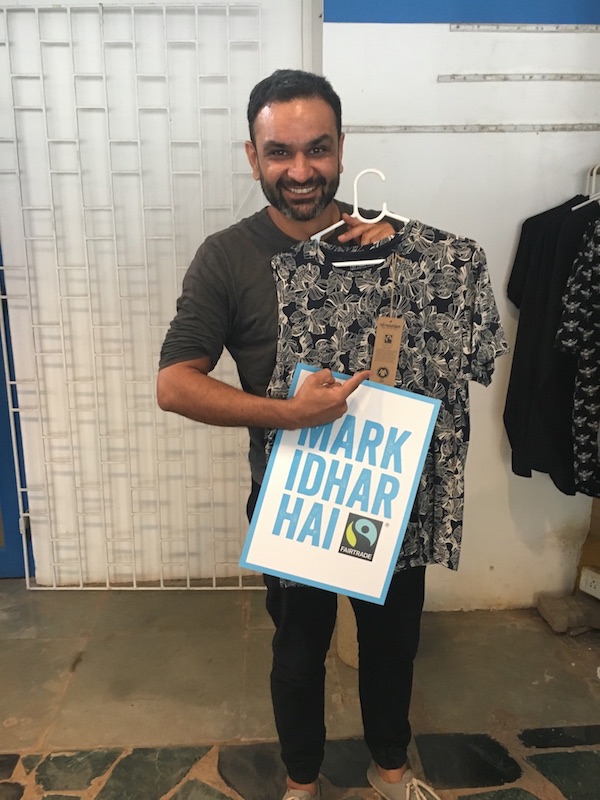

No Nasties makes fair fashion attractive and accessible, and founder Apurva Kothari. Image: No Nasties

No Nasties, India’s first Fairtrade certified fashion brand is part of a small but growing tribe of companies committing to cleaner supply chains. “We launched with the idea of creating a market where Indian consumers support Indian farmers,” says founder Apurva Kothari. What started as a t-shirt company is now a full-range fashion brand aimed at promoting sustainable cotton fashion as an attractive, viable, everyday solution made easily accessible to the average consumer.

No Nasties sources organic cotton directly from a farmer co-operative called Chetna Organic comprised of close to 40,000 small and marginal farmers in 4 or 5 Indian states. It supports a factory that follows eco-friendly manufacturing practices, eschews child labour and exploitative, discriminative labour practices. This gives the brand complete visibility into its supply chain from farm to consumer. To scale up demand and supply, No Nasties also supports other brands interested in going Fairtrade by making its supply chain information freely available and collaborating with them to raise awareness and create demand.

Unfortunately, the market for Fairtrade produce is so small that farmers are yet to see the true benefits of a Fairtrade label. Only a small part of the cotton grown on Fairtrade terms today is sold on these terms with large volumes dumped at cheap rates in the open market.

“As consumers, we don’t know the impact of our purchase decisions, so we're unknowingly or unwillingly supporting practices like child labour and pollution that keep prices low by slashing material and production costs,” says Devina Singh, Campaigns Manager at Fairtrade India.

A look into Fairtrade brand SoulSpace's factories

A major part of Fairtrade’s market creation efforts involve campaigns raising awareness that consumers are part of the solution to end exploitative fashion. Our ask is not that people adopt another, though less harmful brand of consumerism, Singh says, but that they are more discerning when they make their next purchase.

Fashion Revolution Week 2018 saw a handful of new brands, including Deivee and Huetrap committing to cleaner supply chains. Since 2015, Fairtrade India has been partnering with Fashion Revolution to raise awareness about fair fashion with several campaigns like #WhoGrewMyClothes and #SpotTheMark through which consumers could connect more closely with their clothing and hold their favourite brands accountable for the way they do business. They brought into sharp focus the people who grow our clothes and the conditions in which they are made. The ecosystem is expanding with the addition of schools like Vidyashilp Academy which sources Fairtrade uniforms, offices that buy fair trade clothing for events and luxury hotels whose linen is procured from Fairtrade supply chains. Celebrities including Milind Soman and Farhan Akhtar have become ambassadors of the movement.

Fair fashion is no longer a niche segment targeted at do-gooding customers with the message to ‘buy at least one’. For one, it’s much easier to find today, stocked by the same stores, on the same e-commerce platforms, at more-or-less the same prices as mainstream fashion, and in designs that lend themselves to daily wear.

Students of Vidyashilp Academy in their Fairtrade uniforms

Is all this really enough?

The share of sustainable consumption in India is small and the demand for fair fashion comes largely from the export market. This means that though new farmers join the Fairtrade movement every year, this is hardly enough to move the needle, Jani admits. The only way ahead is to have more companies selling a larger percentage of their products on Fairtrade terms leading to better livelihoods and premiums for farmers. This, together with growing customer awareness is what will reform more of the textile value chain and create a profitable market for fair, ecologically sound practices.

The Fairtrade label has been criticised as an extension of the very system that it claims to change, by perpetuating the inequalities in global labour and commodity markets that exclude poor, remote farmers who cannot organise into cooperatives, or afford the fees. It’s been called an honourable marketing tool that helps a company’s image and the egos of affluent consumers who can get behind its evaluation standards. Some critics even ask if farmers actually receive a higher price under Fairtrade and point out that the premium is sometimes insufficient to even cover the cost of investment.

Undoubtedly, a labelling scheme is only a stopgap on the road to lasting change. What we need is a broader strategy from ground up to ensure that there is a systemic transformation in the way farming is done today so that it becomes attractive for new generations of farmers empowered to take control of the cotton from farm to market. There’s a need for more brands to clean up their supply chains, making them transparent and easy to navigate for all consumers, and finally, for a market that’s open to the idea of responsibly-made products.

On the plus side, the pressure on international manufacturers of fast fashion has never been stronger, forcing some to make their supply chain information public and others to introduce limited lines of organic clothing. At a time when many mass-market brands engage in greenwashing with a view to attracting conscious consumers, a Fairtrade label indicates that a brand committed to sustainable fashion is putting its money where its mouth is. It also pushes us to re-examine what we mean by good fashion and puts alternatives within easier reach. And that’s a start.

Images: Courtesy Fairtrade India.

Maya is a social researcher by training. Her writing has appeared in Scroll, YourStory and The Alternative. She is the Founder of Eartha and tweets @Maya_Kilpadi.