How to Read Food Labels and Make Healthy Choices

We live in a time when most of us are accustomed to, what author and environmental activist Michael Pollan calls, ‘eating industrially’ or eating without asking important questions such as “What am I eating?”, “Where did my food come from?” or “How was it produced?”. We are a food obsessed people - we talk about food, love eating it, take hundreds of pictures of it, swap recipes, and watch food shows. Yet we judge our clothes and shoes by far more exacting standards than we do our food.

A good place to start getting better acquainted with your food is the Ingredients label. Did you know that every item of packaged food has to be labelled as per the food safety guidelines defined by the Food Standards and Safety Act of India (FSSAI)? The next time you reach out for any packaged food product, flip it over and read the label.

A window into an invisible world

The Ingredients label is the medium through which the producer of the food interacts and converses with the end consumer - you and I. In the context of the opacity of food production today, the label is a substitute for direct observation by the consumer of how his or her food is produced - something that is rendered difficult by the separation not only of food producers and consumers, but of place of production from place of consumption.

Without the label, we would know very little about the food we eat. So, think of the label as the food’s biodata, revealing all the information you need to know about it: what it contains, whether it’s healthy and safe for you, who manufactured and marketed it, dates of manufacture and expiry, and any safety information regarding allergens or additives. The label is also a vehicle for consumers to communicate their preference to producers: by reading the label and purchasing product without synthetic additives, you send a message to its producer that you value chemical-free food.

Judging a food by its cover

Much of what and how we eat today is influenced by food fads - shifts in food trends that take hold of public consciousness and reverse years of wisdom accumulated by traditional culinary habits. Marketers prey on these fly-by-night food trends that vilify carbs one day and fats the next. A recent study by the American Heart Association had the country in a tizzy recently when it ‘discovered’ that coconut oil might not really be all that good for us. Overnight, the food, which had become comfortable with its ‘superfood’ status in the United States, was knocked off its pedestal.

Think of the label as the food’s biodata, revealing all the information you need to know about it.

For the media-savvy consumer surveying the grocery aisles, it is easy to get tempted by packaging that screams ‘zero cholesterol’, ‘no trans fats’, ‘high-fibre’ and ‘sugar free’. But all those big, bright, bold claims are often misleading, and frankly, not always honest. Unfortunately, food companies are circumscribed by a very narrow set of labelling requirements which allows them to get away with making false or exaggerated claims on their packaging. They are permitted, for instance, to prominently display ‘Whole Grains’ on the packaging even if the product is almost all refined flour. They’re allowed to lure you with phrases like ‘goodness of real vegetables’ when your soup is largely corn starch and MSG and, if you’re really lucky, a glimpse of dehydrated carrot or the shadow of a pea. This is because of lax and outdated labelling laws in our country, inadequate food testing facilities and poor infrastructure to verify the claims food companies make.

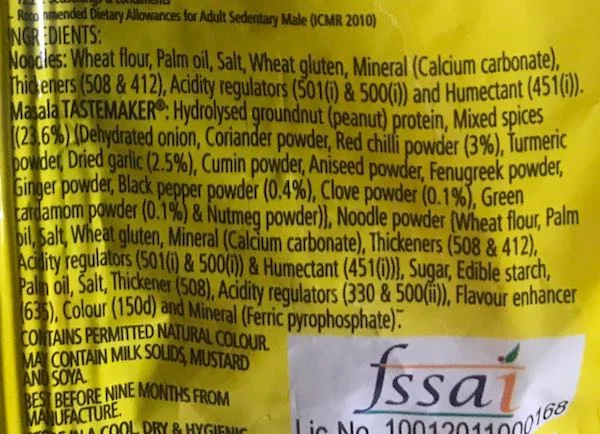

Sample instant noodles label. Image: Eartha

How to read ingredient labels

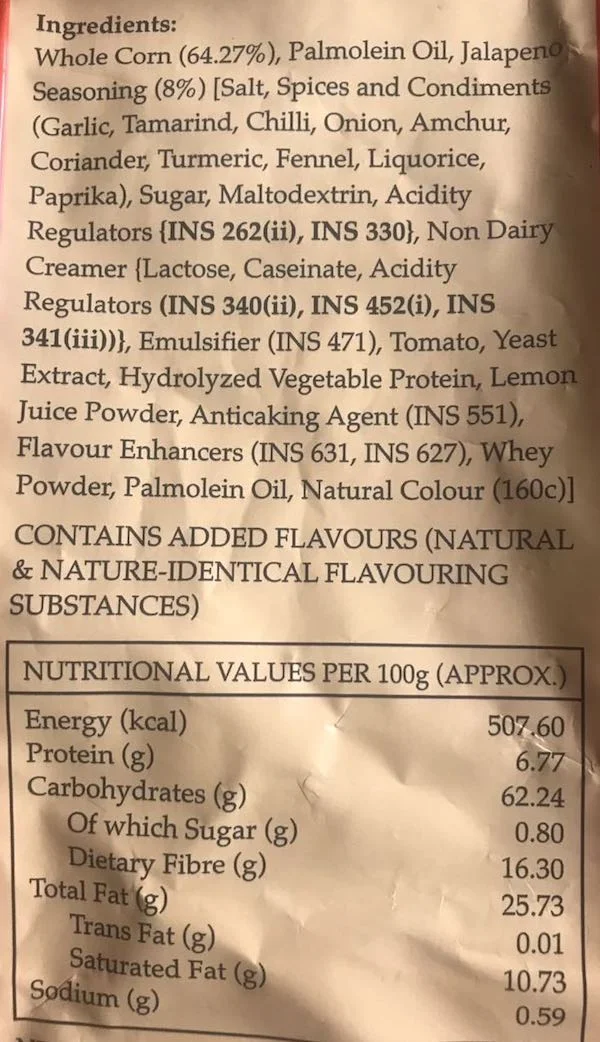

Order of ingredients: Ingredients are always listed in descending order of their quantity in the product. The one present in the largest quantity is listed first and so on. So if a loaf of bread claims to be ‘Whole wheat enriched with Omega-3 rich flaxseeds’, check the label. If whole wheat and flax seeds don’t feature among the top 3 items, it’s likely the loaf is not what it claims to be.

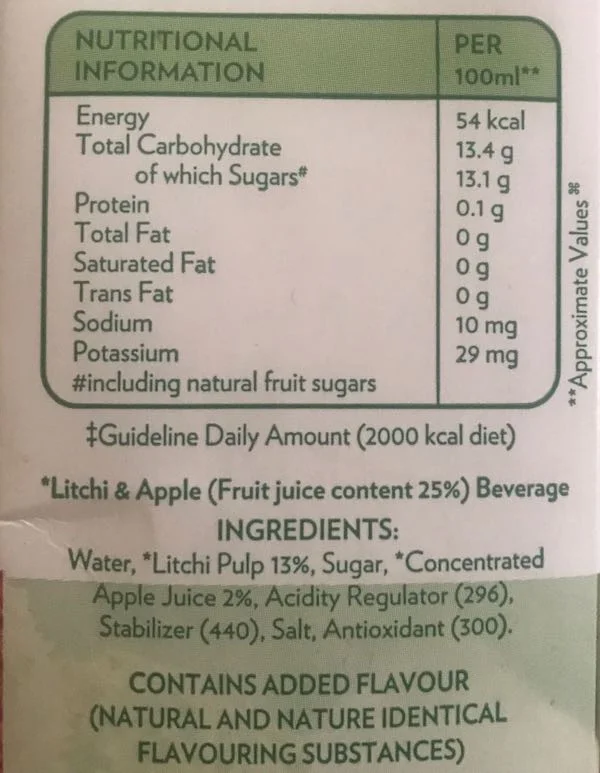

Serving size: The term can be confusing. Nutrition values are usually listed per serving size but a food packet may contain many servings. So, for example, if a package contains two servings and you eat the entire package, you are consuming twice the amount of sugar or salt listed on the label.

Low fat or fat-free: Think you’ve found your dream food? Think again. A low-fat food might still be high in calories. Often, to make up for the low fat content and boost taste, food manufacturers add other ingredients like sugar, flour, thickeners, and salt all of which contribute to the total calorie count.

Sugar-free: Many processed foods and beverages claim to be sugar-free but still taste intensely sweet. These products may be free of pure sugars but are sweetened with artificial sweeteners which masquerade under names like glucose, fructose, dextrose, maltose, high-fructose corn syrup, fruit juice concentrate, maple syrup, aspartame, saccharine, molasses, barley, and malt. Added sugars also include sugar alcohols such as maltitol, lactitol, sorbitol. These sweeteners provide no nutritional value and are a source of empty calories.

Natural flavours: While they may seem like the healthier product choice, natural flavours also contain chemicals. Unlike artificial flavours which are derived from synthetic substances, natural flavours are derived from plant or animal sources.

Sample packaged juice nutrition label. Image: Eartha

Real fruit: Packaged juices that say ‘Contain real fruit’ or ‘made with real fruits’ are rarely what their attractive packaging promises. Juice manufacturers are allowed to make these claims even if their products contain only a single grape. Real fruit juice may be one ingredients in the ‘Fruit Beverage’ but the product will also contain one or more artificial sweeteners, flavour enhancers often innocuously labelled ‘nature identical flavouring substances’ (meant to replace the taste lost during pasteurisation, processing and storage, acidity regulators, and preservatives. The actual fruit juice content is not more than 25 percent.

Low sodium: Salts are similarly deceptively labelled, masked by terms like ‘seasoning’ or monosodium glutamate (MSG). The WHO recommends no more than 5 grams of sodium a day, but the average Indian consumes 119 percent more than that.

High fibre: Dietary fibre is essential for healthy gut action. Unfortunately not all products claiming to contain ‘high-fibre’ are to be taken at face value. For a food to be considered “high fibre,” it is usually processed so that more fibre can be added into it - not all of which may be natural. Fibre additives in the form of maltodextrin, polydextrose and inulin are sometimes added especially to baked goods, dairy products and cereals to bolster their fibre content and to add flavour to otherwise low-calorie food taste better. Foods such as cakes and biscuits claiming to be ‘fibre-rich’ often contain a panoply of synthetic additives including emulsifiers, preservatives and trans fats, celebrity Rujuta Diwekar cautions.

Multigrain: Just because an item claims to be multigrain or ‘made with whole grain’ doesn’t make it healthy. It could still contain a large portion of refined grains or bleached flours that are stripped of all nutrition. Looking at the order of ingredients will tell you what’s the main ingredient in the food. Look for items with 100% whole grain.

Zero trans fats: Trans fats are fats that have been chemically altered - by adding hydrogen atoms to oils - to increase their shelf life and prevent them from turning rancid. The blame for a variety of lifestyle illnesses from obesity to heart disease has been laid at the door of trans fats. Unfortunately, right from our edible oils to confectionery and snacks, they’re in everything today. But, just because a food’s packaging yells ‘trans fat free’ does not mean much. Trans fats often hide behind the two label items: hydrogenated or partially hydrogenated oil. Opt instead for healthy and nutritious groundnut, sesame, coconut or mustard oils for cooking and dressing salads.

Ingredients label on a sample packet of chips. Image: Eartha

Look for additives such as preservatives, emulsifiers and artificial food colouring which appear as the letter “E” suffixed by a 3-digit number. Emulsifiers are used in nearly all packaged foods - from cakes and ice-cream to salad dressings. They help otherwise incompatible ingredients (often oils and fats) blend together, hold foods together and help them retain their structure, and prolong shelf life. Ingredients such as polysorbate 80, lecithin, polyglycerols, and xanthan gum are all emulsifiers. Emulsifiers have been found to disrupt healthy intestinal function and cause inflammation.

Quick tips

- A thumb rule in picking healthy food is to stay away from anything you don’t immediately recognise as food. This rules out all the chemicals.

- Remember, the first three ingredients on the label are what you are largely consuming, so be sure to pay special attention to them.

- Look for less. A product with fewer, mostly natural ingredients is one that’s closest to its natural state and more likely to be free of chemical additives.

Consumer ignorance, laziness and apathy makes it easy for food producers to get away with providing false or incomplete product information. Important food safety information is sometimes offered but in fine print that consumers ignore, or using ambiguous language that's hard to decode. So the next time you’re out grocery shopping, flip the product over and read the label. It might seems baffling at first; it’s meant to. But don’t give up. You’ll become an expert label reader in no time.