An Audit Of Bengaluru's Waste Reveals The Brands That Are Profiting Most From Plastic Pollution

Plastic is a superhero when it comes to convenience and versatility. It can be moulded into thousands of products - from bags and dishes and throwaway cutlery to furniture and clothing. It is lightweight, cheap and durable, and can be designed to be heat-safe and moisture-proof. and increase a product’s shelf-life from a few months to over a year. It’s no wonder then that this material has been called one of humankind’s most influential and practical inventions, on par with the smelting of metals.

From its invention in the late 1800s, plastics have played an integral role in packaging solutions that help transport, store and protect goods until consumers are ready to use them. The need for plastic packaging is the direct fallout of urbanisation, rising disposable incomes, changing lifestyles and consumption patterns. Cheap, single-use plastic makes great business sense in a market defined by fast food, quick delivery, greater distances between producers and consumers, and longer gaps between production and consumption time. It makes for sturdier packaging, increases shelf life, and can be moulded and designed into a variety of shapes and sizes. Maximum profitability for the producer; hassle-free, use-and-throw for the consumer.

Packaged pollution

But, the miracle material comes with a high ecological cost. As it degrades into smaller and smaller pieces that remain in the environment for decades, plastic pollutes our waters and soils, and its chemicals travel through the food chain, passing from plankton to people. So indestructible a material is plastic that with it, humankind has changed the earth’s geological record, creating a new epoch that scientists call the Anthropocene, which is leaving behind a permanent legacy of our activity on the planet.

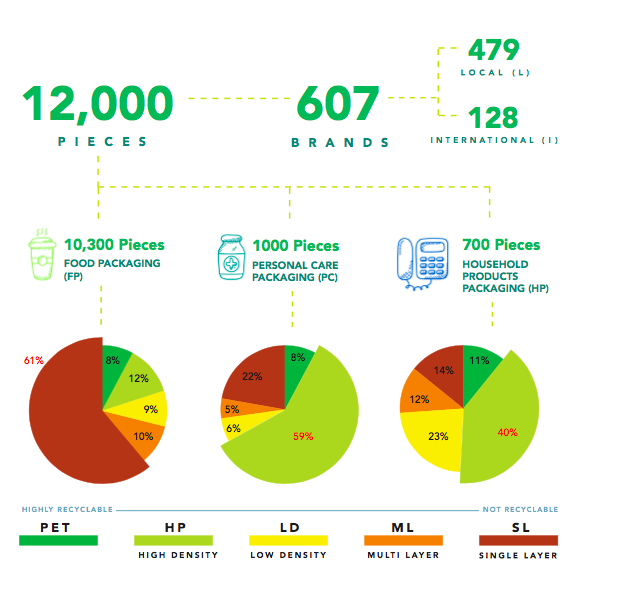

Over 7-% of food packaging is non-recyclable, whereas packaging of personal care products and household goods is of a higher recycle value. Source: Beat Plastic Pollution from Branded Litter Report, SWMRT, GAIA, Hasiru Dala.

Litter with a label

In India, majority of the FMCG products meant for domestic consumption are packaged in plastics. Per capita, Indians use 4.3kg of plastic packaging, a small number compared to countries like Germany or Taiwan where citizens use 42kg and 19kg respectively. Yet, India’s plastic packaging industry is growing at 18% per annum and expected to reach a size of $73 billion by 2020. Per capita consumption is expected to double in the same time, fuelled by a rise in the demand for packaged food, the fastest growing segment in India.

Yet, the ecological cost of packaging waste never makes its way into companies’ annual reports or balance sheets. Without strict policies that hold them responsible for a product’s end-of-life environmental impacts, manufacturers of plastic packaging and brands using it are today absolved of any responsibility to bear post-consumer waste management costs, reduce the use of toxic materials, or redesign their packaging to be reusable or recyclable. In short, they are allowed, with impunity, to externalise the cost of their profit-making activities, often in developing countries where waste management technology and infrastructure are rudimentary, and enforcement mechanisms are absent. This leaves citizens and governments to bear the costs of disposing their waste, and deal with the consequences of pollution from illegal dumping and burning of plastic waste.

In its one-of-a-kind audit, coinciding with UN’s #BeatPlasticPollution theme for World Environment Day 2018, Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternative (GAIA) conducted a 15-city Waste and Brand Audit of domestic plastic waste in India with the aim of identifying the types of plastic packaging dominating our dumps, and the brands contributing most to the municipal solid waste stream. The survey captured three categories of products - food, personal care products and household goods.

In Bengaluru, the audit was led by citizen activists from SWMRT and waste management non-profit, Hasiru Dala. Over 3 days, 120 citizen volunteers examined 12,000 pieces of plastic packaging from domestic sources, and the findings flew in the face of popular belief that most of our plastic waste is recycled. The waste studied that was collected from the city’s Dry Waste Collection Centres (DWCCs). It was dominated by branded food packaging - sachets, pouches, bottles, containers, tubes and others. Majority of these were found to be composed of non recyclable single- and multi-layered plastics or laminates: a composite of at least five layers of recyclable thermoplastic and non-recyclable thermoset making it impossible to separate and recycle. Across 270 domestic and international food brands, multi-layer plastic was the preferred choice, because it is easy to use, lightweight and makes more manufacturing options possible.

It is possible to design food packaging without the thermoset layer, says member of the Supreme Court Committee on Solid Waste Management, Almitra Patel, but food manufacturers say that the middle layer of thermoset helps increase bag strength and shelf life by minimising vapour buildup. Without it, shelf life only 6 months; with it, food products can be stored on shelves for 1 year. But which customer is asking for one-year-old food?

Milk packets made of low density plastic, exempted from the plastic ban, showed up in plenty, exposing a huge gap in innovation for recyclable or reusable alternatives like glass bottles or reusable cans.

Top polluting brands across food, personal care and household goods packaging. Source: Beat Plastic Pollution from Branded Litter Report, SWMRT, GAIA, Hasiru Dala.

True to the law of the vital few, 10 brands comprised 95% of the litter. The top international polluters in the food packaging category are Coca Cola (28%), PepsiCo (15%), Britannia and Nestle (11% each), Unilever (9%), and Bisleri (7%). Local milk producer Nandini made up the worst domestic polluter with 35%, followed by Parle 10%.

The study threw up other telling findings. For instance, it found that 85% of food packaging is for sugary and ready-to-eat processed food. “Most packaged food comprises the very items that we are fighting against in the domain of public health for their role in lifestyle diseases,” says Sandya Narayanan, SWMRT member. Another notable point is that while companies like Coca Cola and Pepsico use recyclable PET for bottling beverages and water, the material choice is not so much the result of voluntary action as it is dictated by the nature of the product. Moreover, both brands have attracted criticism for failing in their own bottle reclamation programmes and stymying government recycling efforts in the interest of safeguarding profits.

Price sensitive personal care and household products were found to be packaged in higher density recyclable plastics (67% and 51% respectively). Again, a few brands led by Unilever, Colgate, Reckitt Benckiser and J&J made up the bulk of the packaging waste for personal care products.

In household goods similarly, 5 brands, led by Unilever, made up 75% of the plastic packaging waste.

Most evident from the audit was the pervasiveness of low-value multi-layered packaging which ends up sitting unused in the DWCCs or dumped in landfills. Says Nalini Shekar of Hasiru Dala, “Every month, more than 90 tons of non-recyclable plastic packaging is sent to cement plants for co-processing, with waste management companies bearing the burden of collection and transport.”

Better for business

While the study did shed light on the offenders, what it highlighted was the urgent need to strengthen Extended Producer Responsibility norms that make producers and users of plastic packaging responsible for the entire life-cycle of any packaging they put into the market, especially in its post consumption phase. Broadly, this would mean companies will have to institute takeback and collection systems for plastic packaging waste at points where it is generated, as well as infrastructure for recycling it in an environment-friendly manner. Simultaneously, with the view to eventually phase out non-recyclable plastic packaging, R&D should be geared towards identifying sustainable alternatives.

Strengthening existing waste management infrastructure is another avenue for brands to fulfil their EPR obligations. Says Shekar, “Rather than creating a parallel, private waste handling system, manufacturers must work with governments and civil society organisations to improve the existing waste collection and recycling network which rides on the backs of skilled informal sector workers who, in Bengaluru, recycle close to 4000 tons of plastic waste a day.” This would mean that brands could finance the upgradation of DWCCs with better infrastructure and recycling technology, support the operating expenses of DWCCs especially in Tier 2 and 3 cities until they break even, or enforce safer labour and pollution control standards.

At present, industry actions to improve take-back, collection, R&D for better design, and environment-friendly recycling, if undertaken, are voluntary, often subsumed under the umbrella of CSR, without any accountability to shareholders or civil society.

But, existing laws of the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change - the Plastic Waste Management Rules 2016 and 2018 and its parent law, the Solid Waste Management Rules 2016, carry progressive clauses that make it mandatory for brand owners and producers who put plastic packaging waste into the market to institute mechanisms for its collection, takeback and recovery so that it is kept out of landfills.

The laws also stipulate that the primary responsibility for phasing out plastic packaging lies with brands. It makes them liable to redesign their packaging with a view to finding sustainable alternatives to non-recyclable materials which, it adds, are to be phased out within two years of the date of the law. The focus of business, mentions the Policy Resolution for Petrochemicals 2007, should be on ‘safe’ not ‘cost-effective’ plastic packaging.

Today, several formulae have been proposed to address the menace of plastic pollution: some like waste-to-energy plants fall within the realm of inefficient in the Indian context, besides being financially and environmentally expensive. Others such as turning plastic waste into roads, irrigation pipes and paver blocks, while good as stopgap solutions, are slow to take off and fail to stem the problem at the root.

Says Narayanan, “Our policies do offer direction, but their implementation is being ignored by industry in collusion with the government. As consumers of FMCG products, consumers need to become aware of these rules, understand them, and work with officials if we’d like to see any policy implementation take place.” She’s right. Policies like the plastic ban which had their inception in citizen-led movements have been effective in curbing the entry of single-use plastic carry bags and cutlery into the market and thereby, into garbage dumps. The same level of involvement will be necessary to ensure that enforcement of EPR norms is regulated and monitored more stringently so that companies no longer profit from pollution, but put their resources towards better systems of producing and delivering packaging.